📚 Stoicism & the Cobra Effect in The Folding Knife by K. J. Parker

A spoilerific reflection on a book Patrick McKenzie called "the best low-fantasy public health writing you'll ever read."

People always say Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City is the perfect book for me. It’s true that I love me a good infrastructure-oriented fantasy, but every time I tried to read it, I bounced off. When I mentioned this to my friend Josh, he was the first person who reacted helpfully.

He suggested I read K. J. Parker’s other books — the ones that make less of an attempt at humor.

I devoured The Folding Knife in a weekend and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. This review (rumination?) is necessarily going to include spoilers, so if there is any chance at all you’ll read a politics & economics heavy fantasy novel with no magic that’s vibes like Venetian and Athenian politics, I encourage you to go read it (bonus points if you use my affiliate link) and then come back and discuss it with me.

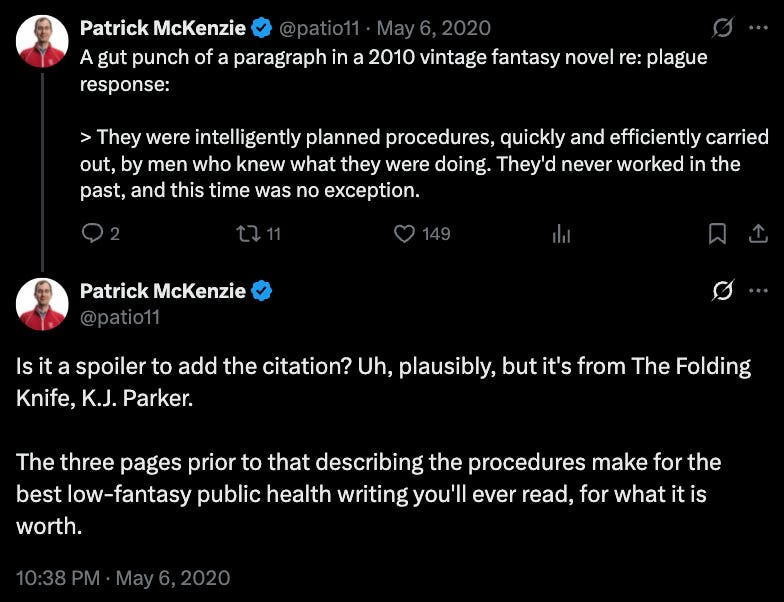

The Folding Knife is the most painfully true book about pandemic management I’ve ever read (especially compared to Earth Abides, which I’m still disappointed I didn’t like1), though the plague takes up probably less than 1% of the book. It was mentioned by Patrick Mackenzie in May of 2020 thusly:

But it’s also in some ways the most stoic book I’ve ever read, although stoic philosophy is never mentioned. The closest thing we get is this, from a letter written by the protagonist’s nephew:

We’re alive precisely because we’re lost; because we’ve wandered into the depths of the forest, and no bugger knows where to find us. There’s probably a deep philosophical truth in there somewhere.

The protagonist — the scion of a powerful family in a city-state that resembles Athens — accepts pain and hardship as part of life. Early in the story, Basso beats the crap out of a soldier and ends up deaf in one ear as a result of the punishment. Later, he loses the use of most of his hand defending himself from his wife’s lover.

But those are physical pains. The emotional pain he endures is much worse.

Basso kills his wife’s lover in self-defense, but unfortunately for literally everyone in this world, that man was his brother-in-law. His wife, Basso’s sister, knew about his chronic infidelity and didn’t care — but she loved him dearly. And the sister (Fausta Tranquillina Carausia) spends the rest of the book doing everything in her power to make Basso suffer. She sends assassins after him. She works hard to stymie him at every political turn. By forcing him to remarry, she is the ultimate architect of not only his downfall, but the economic crippling of an entire region of the world.

At no point does Basso ever make the slightest effort to fight back, because she is his sister, and he loves her more than anyone else in the world.

Here’s his own reflection on the matter:

A man who faces opposition must either fight or accept. I refuse to fight my own sister, to defeat her by any means necessary. Because I love her, I can’t refuse her anything, and what she wants is to hate me. Fight or accept. Accept.

He stymies her plots to the best of his (considerable) ability, and he doesn’t let her stand in the way of her son’s growth (because he loves his nephew as well). But fundamentally, he lets her dictate the pace of their conflict, and though it costs him and many others, he has this wonderfully stoic sense of duty that I’ve never seen anywhere else in fiction.

On the subject of his marriage, The Folding Knife also has an unusually positive opinion of arranged marriages. Most of them evolve into love, and they’re painted as a critically important part of how the high society (and therefore government) of the republic works:

Arranged marriages, amortised loans and the Republican Navy are what keep this city from going under.

But this isn’t really a book about marriage or love. It’s a book about economic management.

He quickly got the hang of the exchequer, double-entry bookkeeping, currency conversion and elementary accounting procedures. It was boring, but no more so than literature or philosophy, and unlike those two annoyances of his youth, he could see there was a point to it.

Basso is treated as a virtuoso economist and political player. He plays the senate and the money markets like a flute, basically invents paper currency, and speedruns most of the common wisdom of our time.

As one character pithily puts it:

“I think that if someone tried to rob you in the street, you’d pick his pocket, sell him a better knife, and probably offer him a job as a tax collector.”

Other than failing to deal with his sister, there was only one moment where it felt like Basso really flubbed: understanding incentives.

“In that case, I suggest you keep your streets swept, and offer a bounty of a florin a dozen for rats’ tails. It may help. It’ll almost certainly win you votes.”

Basso’s smile widened, to reveal all his teeth. “I might just do that,” he said. “Jobs for poor people, and it may even be useful. I think we’ll just have to take our chances with the beef imports. If we get another outbreak, at least we’ll know what to tell people.”

I go back and forth trying to decide whether I think K. J. Parker slipped this in as a subtle nod to Basso’s coming downfall, or if Parker really did think this was a clever solution to the problem. But the exchange really was very on the nose.

For those not familiar with this famous incident, I recommend this great Atlas Obscure article: The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre of 1902 Did Not Go as Planned.

The real life story goes something like this: After his scheme for a new income tax fails, French Minister of Finance Paul Doumer heads to Vietnam to help out there. He tries to improve the housing situation by adding indoor plumbing. The colonial government lays miles of sewer pipes, which end up being rodent paradise. Plague pops up, as the plague sometimes does when there are lots of fleas and rats around.

So what does the government do? Put a bounty on rats. It seems to work at first — over 4,000 rats a day are killed. But as Goodhart’s Law aptly states, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” The government wanted a lot of rats killed per day, so that’s what they got. Over 20,000 rats were killed on June 21 alone.

Astute readers, and those already familiar with the Cobra Effect and The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt, know where this is going.

It turned out the hunters would rather amputate a live animal’s tail than take a healthy rat, capable of breeding and creating so many more rats—with those valuable tails—out of commission. There were also reports that some Vietnamese were smuggling foreign rats into the city. And then the final straw: Health inspectors discovered, in the countryside on the outskirts of Hanoi, pop-up farming operations dedicated to breeding rats.

One of the really neat things about The Folding Knife is that I didn’t know where it was going. I spent the first chapter thinking the protagonist was going to be some kind of combat savant, because he beats the hell out of the soldier at a young age. But his fighting prowess comes up only once or twice, and after that first incident, it’s always sweaty and grubby and bloody. He goes about mastering combat skills in a fairly sensible way in his youth, retains some of the important lessons, but isn’t a soldier and isn’t trying to be.

Basso is a merchant prince. And until he makes 2 critical errors, an excellent one. So excellent that I spent the second chunk of the book thinking “ah, this is just competency porn. The protagonist has it super easy so that we can have a cozy economic theory book.”

Truisms like this are sprinkled throughout the text:

“A good deal is where both sides make a profit,” he said. “That way, both sides will want to deal with each other again.

To be clear, I am totally down for a cozy economic theory book. Nathan Lowell2 has a bunch of great ones. So I was not at all expecting it when Basso’s second wife, an immigrant from the ungovernable tribes across the sea, utterly betrays his attempts to conquer her homeland, extract its mineral wealth, and in the process make life better for the natives.

I enjoyed how it’s presented in precisely this order of priorities, too. There’s a metaphor about capitalism here, I think. Basso and his nephew both often reflect on how the unintended but happy consequence of seeking power and money is that it makes life better for everyone.

Here’s one such example:

if the value you put on human beings sinks low enough, you stand a fair chance of establishing universal peace and prosperity. Bring those values down, and everybody can afford to be happy. It’s only when you start packing out the shopping basket with luxury goods such as freedom and dignity and the right to self-determination that you price poor folks out of the market. It makes sense, once you’ve seen it for yourself. If you’ve never seen it, of course, it must sound barbaric.

And to Basso’s wife, it does indeed sound barbaric… which is why things go off the rails. She takes “live free, or die” to its logical extreme, and I believe that we the reader are meant to reflect on how much we — as Americans in particular, given our history, although K. J. Parker is an Oxford-education Brit — really mean it.

Stupid woman, he thought. “You realise what you’ve done,” he said. “Didn’t you see the reports? They’ve got the bloody plague in the villages now. It’ll kill half your precious people.”

“I know,” she said. “But we’d3 rather die than be conquered.”

That was so ridiculous, so utterly stupid, it made him want to scream.

The irony here is that the reason he married her was that she wasn’t cowed when he yelled at her. If he had married a sweet, biddable local noblewoman, his plans probably would have played out alright.

He would have ended up with different political problems, of course. But I suspect they wouldn’t have surprised him the way his wife killing Basso’s nephew, boatloads of soldiers, and uncountable villagers by teaching her countrymen how to deliberately infect the cities with plague.

But it's interesting how in the end his downfall really was the sister’s scheme to force him into a marriage he didn’t want, and how he couldn’t be ruthless enough to put the needs of his country over his sister’s life or desire to see him suffer.

He wasn’t willing to defeat her, and so countries ended up in ruins.

But note that this isn’t a book about how women are evil. My take was that it was a book about how Basso would have been better served by treating the women around him like people. Like equals worthy of his full attention and regard.

The other irony is that the main reason Basso was building an empire in the first place was because he calculated (probably correctly) that the eastern empire was going to be coming to conquer the region soon, and he wanted the local countries to be able to stand up against them. So it’s unlikely that the ‘barbarians’ would have ended up freed for very long.

Unfortunately, this book is a stand-alone novel, so we end on the note of Basso fleeing famine, essentially destitute, everyone he’s ever love either dead or estranged. But he has his wits, and the crumbs of past connections, so he has prospects to work himself back up and perhaps build up another country into a power that can stand against the East.

It rather reminded me of Kipling’s If—

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

[…]

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

I like to imagine he succeeds in fending off the Empire, because whatever else his many faults, Basso is a man fully capable of self-reflection, and realizing where his mistakes were, and updating his behaviors for the future.

My favorite?

When he realized he should have abandoned his plans for conquest sooner; specifically, when his mentor and advisor died. Sometimes quitting is the right choice! And it was really nice to see a fantasy novel where a protagonist got burned because they didn’t quit when they should have.

“Nice” in the sense that I felt super weird at the end, because I really did expect a second book and I do generally expect a happy ending. But this book was philosophical and thoughtful enough that it felt like it made its point, ending the way it did. It made me think more than a neat little conquest would have, for sure.

And the cool thing was that when I picked up another book by K. J. Parker called Sharps, it felt like a sequel even though it wasn’t. They’re set in a different time period; Sharps vibed in a sort of 18th century way, while The Folding Knife felt positively Athenian. And the big empty area separating the countries was different — in Sharps it was a “demilitarized” zone chewed into uselessness by shepherds, while The Folding Knife was much more naval. But in a lot of ways, Sharps felt like the story of “what if Basso’s plan had worked, and the bank won?”

I see why a guy like Patrick McKenzie, banking nerd extraordinaire, liked K. J Parker. I am somewhat less qualified to advise Stripe on its corporate strategy than Patrick, but I liked it too.

I liked it even better after I finished Sharps — and that one, I won’t spoil ;)

To read more about why I stopped in the middle of Earth Abides, check out my micro-reviews of chunky books I read back in April & May.

Here are my micro-reviews of chill and cozy fiction I read after I had my daughter, including Nathan’s Trader’s Tales from the Golden Age of the Solar Clipper series.

Note the “we” here, because I strongly suspect nobody asked the regular villagers.

Your hyperlink to "The Folding Knife" goes to Josh's website, not to an Amazon affiliate link, FYI.