🌲 The Konik Method for Organizing Electronic Notes

An update to the award-winning 2022-era Konik Method for Making Useful Notes, now that AI can do the grunt work for us.

Back in 2022, my article outlining the Konik Method for Making Useful Notes won Obsidian October and was widely shared in notetaking communities — although it was written before my migration to Substack so alas, all the comments are lost. Now that it’s been three years (!) I thought it might be useful to explain how technological changes (like the rise of AI) have changed my workflow.

Warning: there are enough photos that Substack is freaking out again about how the email is too long, even though I put all of my prompts and templates into gists on GitHub, so once again I implore you to click through to the live version of the website.

there are a lot of different reasons to take notes

My fundamental process hasn’t changed in the last three years. I used to have a really complex chart for where I got information from, and how I got it into my notes. I read PDFs in Zotero, saved tweets using the.rip, read ebooks using Kindle. Now I mostly just use Readwise Reader, which wasn’t even available back in 2022; it supports my RSS feeds, my Substack newsletters, my ebooks, my stuff from Twitter and Reddit, all of it. In the last three years Reader’s gotten a lot better, partly because of AI-backed features like improved PDF-to-text parsing… and partly because I helped hunt some bugs and helped the development team get them fixed, now that they gave me a job 💚

But despite the technological advances, note taking for me is still pretty simple: I start with a goal, I record key information and insights, and then I organize it and refer back to those notes as needed.

At this stage of my life, most of what I find useful is stuff I found before I knew it was going to be useful. I like to front-load the effort — very rarely do I go looking for information where I actually need to go learn a bunch of stuff from a book. Particularly in an age where AI-powered, well-sourced Deep Research type tools exist, I just don’t spend a lot of time refering back to material because I get my answers immediately and then move on.

So I prefer to come at the process of note making from one of three angles. “Pleasure reading,” “reading to expand my horizons,” and “reading to kill time” — which is subtly different from pleasure reading in that it’s more like “skimming passive feeds” than “snuggling in with a cozy piece of fiction.” There’s a lot of work that goes into optimizing a passive feed to actually have useful stuff instead of ragebait, and the social media landscape’s ever-changing algorithm doesn’t help, but I do my best to curate my feeds so that when I don’t have the time or bandwidth to sink into a book I’m still doing something vaguely useful instead of just winding myself up about whatever.

If I’m making my way across a long parking lot on my way to pick my son up from daycare, I’ll sort through my RSS feeds. If I’m waiting by myself at the doctor’s office, I’ll read an article or two from my queue. If my kid wants to learn about the world’s most toxic animals, how tanks got invented, or how Victorian baking worked, we’ll put on a documentary. If I have more time and energy, I’ll often read a book in my hammock or in bed. In another few years, maybe my kids will be chill enough for me to read a book upstairs in the living room again.

But no matter what I’m reading, all of my notes end up in one of two formats. I’ve already explained how I make analog notes…

🌲 The Konik Method for Making Analog Notes

Last week, Robert DePriest mentioned that he’s torn between using sticking with digital notetaking, and adopting a physical notebook and notecard-based modern zettelkasten. “I love the feel of pen and paper but end up going back to Obsidian for efficiency. But maybe efficiency isn't the ultimate goal? Anyone else struggle between digital and analog? Is there a happy m…

So this week, I want to share my digital note taking process.

taking notes begins with learning and thinking

Most of my actual thinking happens when I’m reading. Using Readwise Reader (who I started working for after I developed this basic process) I highlight and annotate a digital file. This can be a PDF, or an email, or a Twitter thread, or an ebook — it doesn’t really matter. If you prefer to read in Kindle, or Zotero, or Kobo, or wherever, this basic process should still work for you as long as there’s a way to export highlights. Hell, if you’re feeling frisky1, you can probably read on paper, take a bunch of pictures, and force an LLM to process them into a tidy file.

I’m going to focus on long books for this article, mostly because they’re the hardest (and most important) to actually process, since they’re read over a couple of days or months and the notes tend to get unwieldy if you’re not careful.

My habit is to highlight anything I want to see again, and ignore the rest. If I’m in a hurry, I’ll grab the whole paragraph, but otherwise I try to focus on something more targeted. I try to leave myself a note about why I grabbed the quote, which boils down to a couple of narrow categories I’ve developed tags for:

#bmf, or “backwards mapping fiction,” is my shorthand for something that is connected to something from a fiction book. These are usually pretty obscure, but the most recent example was a line in a book about paleontology that discussed how gritty grass is compared to leaves and fruit. This had implications for dental evolution and reminded me of the nightsheep from L. E. Modesitt’s Corean Chronicles. There’s a minor plot point in the first book about the protagonist saving a lamb by convincing it to drink milk with ground-up quartz in it, because the nightsheep evolved to eat vegetation with high levels of… well, you get the idea.

#addendum is the tag I use when something I read relates to something I’ve already written a lengthy article about, for example all the neat things trees can be, sumptuary laws in various cultures, and human sacrifice.

#xref is for when something relates to something I have notes about but haven’t actually written an article about.

#articleseed is the tag I use when I have an idea for an article that is mostly not related to all of my other notes, or is a specific idea for a relatively unique spin on a concept that I can use other notes for but isn’t captured in a core note yet.

#storystem is for when something gives me a strong idea for a piece of fiction I’d like to write. Although currently I write a lot less fiction than I used to, I’d like to get back to it at some point and have been dipping my toes into short fiction again.

#share is for bits of information I want to share with a specific person or group of people, like a friend who is really nerdy about something I’d never write an article about.

#aphorisms is for the rare bits of advice on good living that seem timeless and I want to remind myself of again and again.

My point here is not to suggest that you should use my tagging schema — I sincerely doubt #bmf would be of interest to most people, even though those are my favorite bits of information to stumble across. My point is that it is helpful to have a tagging schema that is customized to your preferences and reasons for reading. What are you interested in? What motivates you to take notes on books at all?

it’s good to reflect on what you recently read

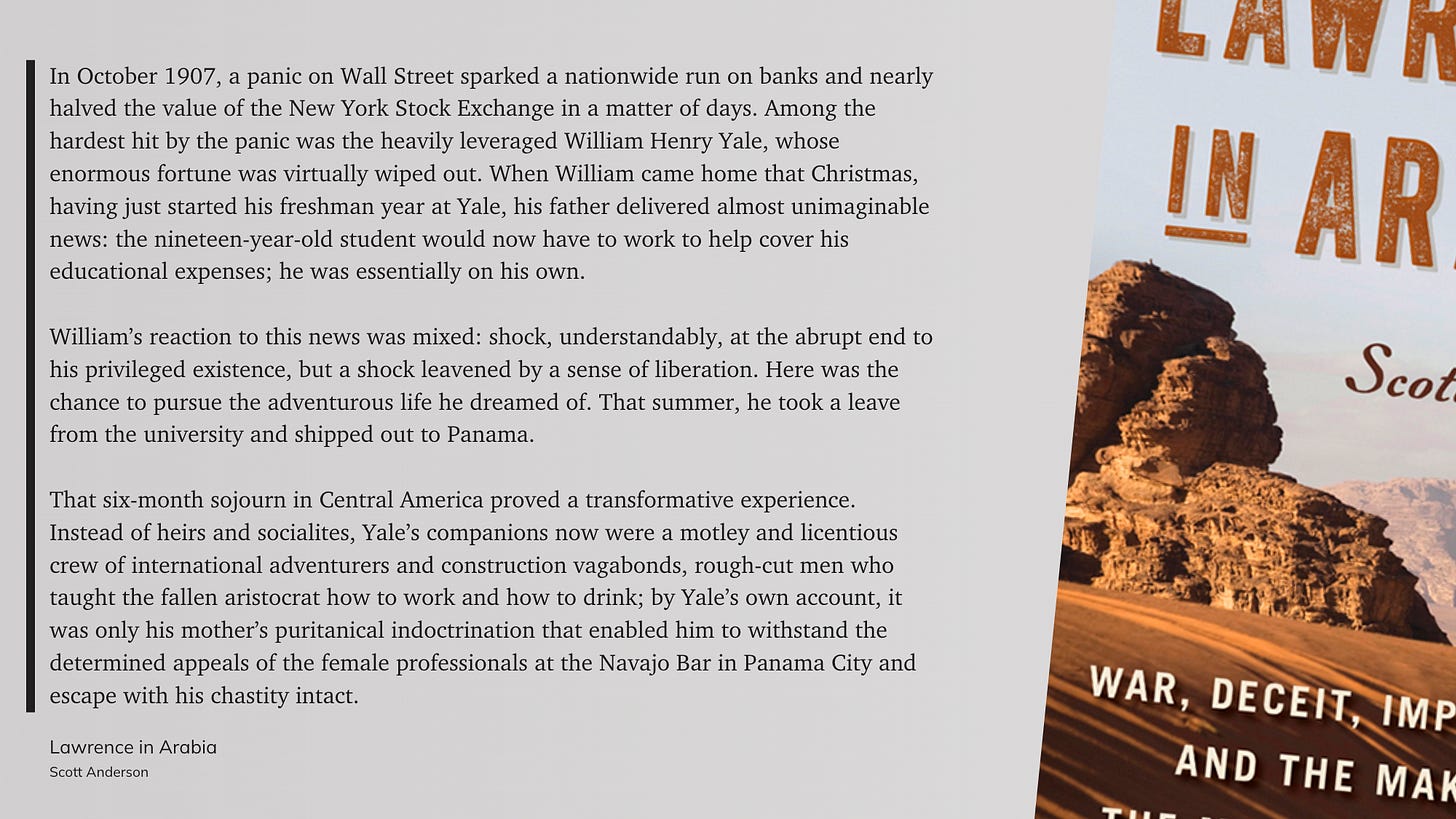

As I read long books, I often fire off a note related to a section I just got through to help solidify my thoughts, then link to the social media post from the document note of a book or the annotation. Here’s an example of a social media post synthesized from a big chunk of Lawrence in Arabia (which I ended up not finishing because I find Lawrence himself rather depressing).

One highlight that inspired this line of thinking is this huge quote about the 1907 stock market crash.

But you may note that, as long as this is, it doesn’t go into much detail about how Yale was raised as a rugged individualist type of man, in the style of Teddy Roosevelt. That comes from a totally different section of the book, and while I have a highlight serving as a source, the notes I took on paper are really speaking to the gestalt of the man that I had remembered as I was reflecting on that quote about cooperation leading to triumph.

I end up collecting a lot of random thoughts this way as I read through the book, and it’s important that I file them properly or they get lost in the shuffle of ephemeral social media post (or physical note… but that’s why I usually share these notes digitally; to make them easier for me to find later, because they’re filed digitally).

most LLM help is best after you’re done reading

Sometimes I like to look things up as I read, especially if I come across a place or a person I’ve never heard of but the author assumes is common knowledge. Most of the time, though, my heavy AI usage comes after I’m done. I use Reader to “chat” with my documents and highlights to find things I vaguely remember, using what amounts to fancy semantic search. I use other LLMs to actually organize the big pile of notes I’m left with at the end of a book.

This somewhat disjointed pile of notes needs to be processed before being used for various projects, if only so I can remind myself of what they even are. All the stuff I’ve noted can be cross-referenced with other things actually needs to get cross-referenced with those things. The article ideas need to be researched further and expanded into articles. Things I wanted to share with specific friends need to be resurfaced and passed along. Story ideas have to get filed with the rest of my inspiration fodder.

Organizing all of this is time-consuming but not terribly intellectual. I’m just following directions from my past self as I review a huge pile of highlights and annotations.

The directions from my past self, as outlined in the original Konik Method for Making Useful Notes, boil down to this:

Convert the evidence/quote into a concise claim statement

Use present tense, declarative statements

Make claims specific and actionable

Ensure claims are searchable (use keywords someone would search for)

Keep claims under 10 words when possible

Focus on the main takeaway, not peripheral details

Ensure claims do not repeat, each should be unique

If there is an annotation (outside of the > format), emphasize whatever the content of the annotation focused on.

It’s hopefully obvious why doing this comes with benefits. It makes the file easier to navigate, for one thing. But as much as I reap benefits from these headers, slapping a 7-word summary onto the header of a quote can get a bit rote after awhile, no matter how interesting the content.

It’s a perfect job to outsource — and don’t worry, I still get the “extra touch” of re-reading everything, because I have to check the outputs… which I would do whether I was asking one of my teenaged babysitters2 to process this file, or an AI.

I say “file” because I like to work out of markdown files in my favorite note-taking app Obsidian, but you should be able to follow this basic process in whatever format you prefer. You can usually import and export from other notes apps either by copy/pasting or literally exporting a markdown file, or you can use AI directly on the file (as long as it’s not too long or the AI is particularly well-integrated).

In similar vein, a variation of the prompt I use should work with any of the major LLMs, although obviously some are dumber than others and have different quirks when it comes to their UI. I personally prefer to use the Comet browser3, because:

I like how the UI lets me go back and review the chain of reasoning.

I like that it lets me use most of the major models.

I love that I can store my preferred prompts — including what connections are toggled on and what model I prefer to use — as slash commands.

I enjoy having the chatbox in my sidebar, so I don’t need to context switch

But that said I verified that this basic workflow works fine in Claude and ChatGPT, I’m not doing anything here that’s particularly crazy. If you go my route and use Comet, note that you’ll need to use the “Labs” option, otherwise it won’t actually generate a file… and for anything bigger than like five highlights, you really need it to generate an actual file.

Then put that file somewhere you can do more stuff with it.

after processing your notes, actually review them

Once the LLM is done with my file, I usually put it in Obsidian — which is where I got the raw dump in the first place, thanks to the Readwise plugin and my quirky export template.

I have a couple of reasons for preferring Obsidian, but for the specific task of making >100 headers with a LLM, the main one is that I am a paranoid soul.

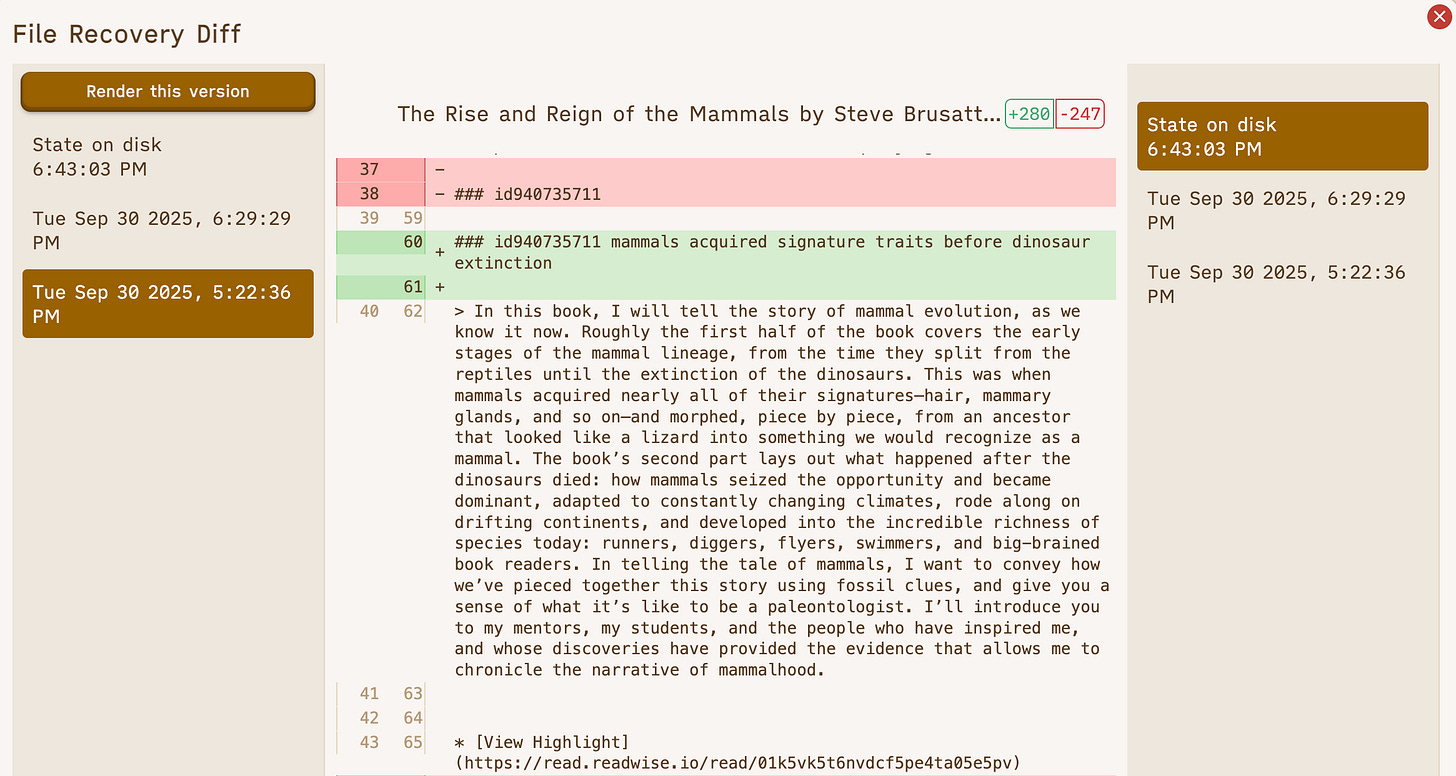

Obsidian makes it very easy to check that the LLM hasn’t corrupted my file with gibberish with one wonderful plugin: Version History Diff by kometenstaub, which is the primary reason I feel safe using LLMs for this sort of task on such a big file. Here’s an example change, taken from my notes on The Rise and Reign of the Mammals by Steve Brusatte… all 15,000 words of them.

For those not familiar with diffing files, the red - lines mean that line was deleted. The green + means it was added. So you can see that the LLM replaced the old id with a new one (with the same number, thankfully) that adds a useful header. Crucially, you can see that it did not mess up the “view highlight” link or ever-so-helpfully edit or summarize the actual text of the quote.

Like most of my nonfiction book notes, this file is big. But it only takes about a minute for me to skim this diff view and check to make sure the numbers line up and nothing got erroneously removed — which happens! Once, before I fully refined my prompt, the LLM helpfully removed all of my “view highlight” links, which made it a lot harder to go look at the full document in Reader and see surrounding context for a particular quote I had flagged.

And, look. The headers aren’t as good as what I’d come up with on my own. The LLM can’t see inside of my head, particularly if I’m in a hurry when I made the original highlight and skipped making an annotation. Sometimes I’m out walking just double-tapped my earbud instead of stopping and typing a note, because I know that I will remember why I made it. But the goal here isn’t to completely replace myself in the writing process, it’s just to make it easier for me to engage with a 15,000 word file distilling the most actionable and interesting bits of a much longer book — in this case, closer to 175,000 words.

So once the LLM has had its turn, it’s batter-up for me to go through and tweak the headers to match what I really want. Sometimes, this means telling the LLM to fix something it systemically flubbed this time that it didn’t mess up on a previous book.

LLMs have non-deterministic outputs. I’m not going to lie to you and say this prompt works perfectly every time. Frankly, I only bother using it on big files because it doesn’t really save time for the little ones. But sometimes needing to say things like “you didn’t actually output the file, make the file” only takes a few more seconds, as annoying as it is, and in the end, I find it helpful, because…

Readwise + Obsidian + AI = 🚀

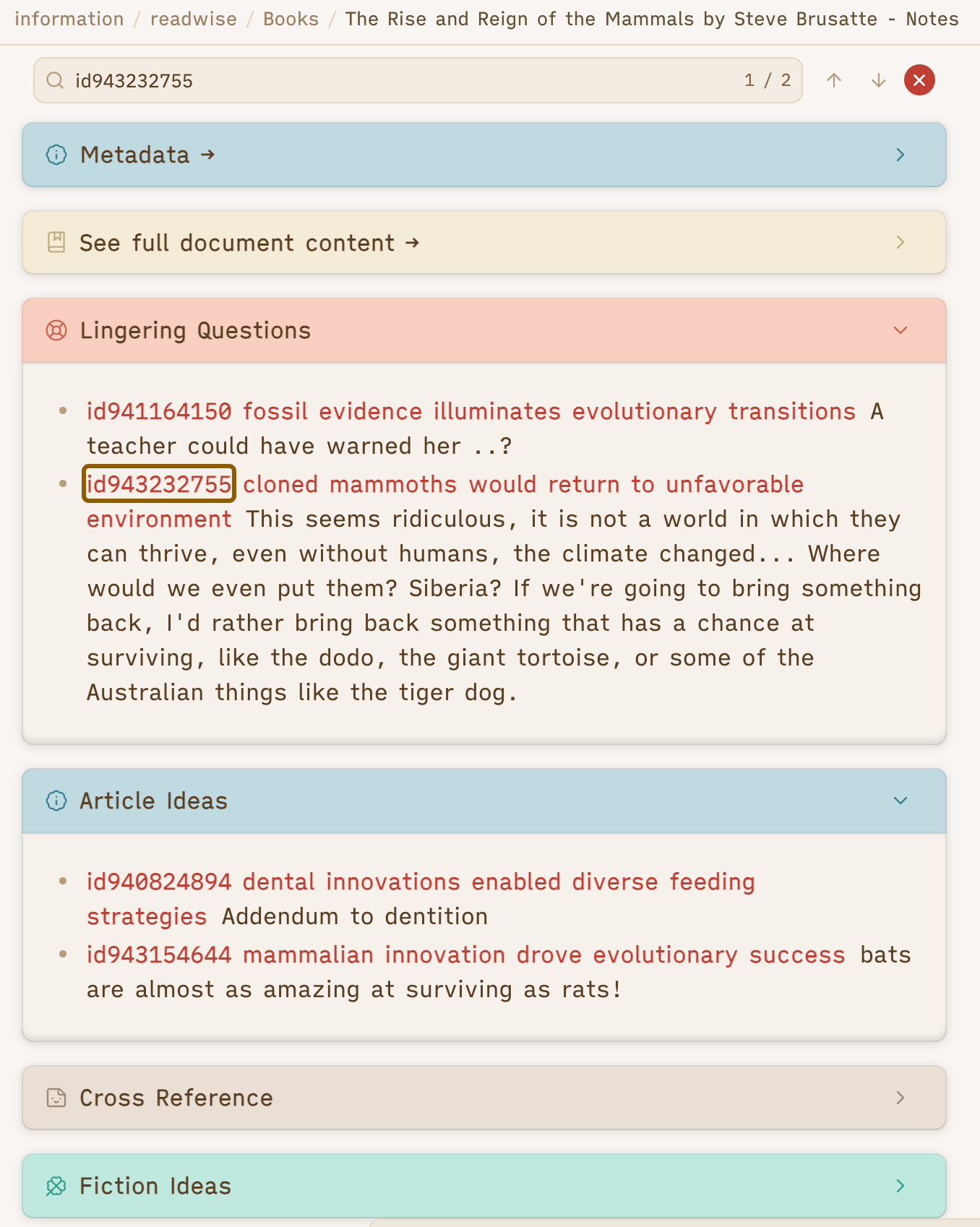

Having even a sub-par table of contents makes the task of dealing with an overwhelming pile of notes much easier, not least of which because the part of my prompt I didn’t mention yet is where it gives me a tidily organized starting point from which to start dealing with all the notes I left myself… because it pulls out my action items and shoves them at the top of the file. It’s a boring bit of copy-paste, but also a remarkably useful, automatically generated to-do list.

Like so:

Next, I’ll move the file out of my Readwise database and into its own special “annotated” folder. Then I’ll go through, spin out sections into atomic cards using QuickAdd and the zettelizer script (I have my own variation, of course), cross-reference the things that need cross-referencing, write the articles I wanted to write and continue engaging with the book over time. You’ve seen the fruits of this process in articles like my review of Civilizations of Africa and When Royal Marriages Keep Power Inside the Family. Stay tuned for articles about what bats can teach us about finding our niche, how incredibly good human groups are at taking on huge hunting projects, and everything you didn’t know you wanted to know about how ancient Assyrian wine co-ops mirror modern subscription services.

Straight from my notebook to your inbox.

I haven’t had a chance to try this myself but I fully intend to; if you beat me to it, report back!

Back when I first learned about Eisenhower matrices, I remember thinking “Outsource?! I’m not some business exec, how on earth could I ever outsource anything? That sounds crazy expensive.” But ever since I started having teenagers come over to watch the kids, I have been making lists of simple things that a reasonably industrious teenager can do while my kids are asleep, and it is amazing. They seem happy to have something productive to do instead of doomscroll their phones, and often learn a new skill like powerwashing or baking.

I don’t actually use most of the agentic abilities of the Comet browser, because I am a paranoid soul and there’s relatively little I need an agent to do for me. But I do strongly prefer Comet’s UI to most of the other LLMs I’ve tried, so I just use the Comet browser in lieu of Claude desktop or whatever, and don’t log into any sensitive accounts. I mostly use it for double-checking things when I’m writing, actually — it’s better as a grammar-checker than most others I’ve tried, and actually works on my Substack drafts in all their footnoted glory… unlike the other LLM interfaces.

I also like to make my notes within Zotero and connect them with my daily thoughts in Anytype.

Thanks for your inspiring approach.

This type of post is my absolute favorite! I'll never be thankful enough that you introduced me to Obsidian back in the day :))

It's entirely amazing to me that, while we are using the same tools, for the same goals, with very similar materials (books about humanities stuff), our processes are complete opposites. I could never keep up with such an organized and refined level of notes, but i've found ai to be helpful in dealing with my 100000 words of much more loosely organized notes.