🎓 When Canals and Bridges Fail Us

Sandstorms, droughts, and big big ships have implications for the carrying capacity of the world. Which is to say: how many people can be alive at once.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Panama over the years. When my husband and I were on our honeymoon in Costa Rica, we ran into an American family who were visiting from Panama. Panama disease changed the banana, and so it came up a lot in Banana by Dan Koeppel1. Panama was also critically important to the ‘coming of age’ process for William Yale, one of the only people in Lawrence in Arabia2 whose life I found compelling and interesting. His life was transformed by six months working in Panama during the canal-construction era, after his family went broke during a financial crisis. The world of “construction vagabonds” and rough cosmopolitan life in Panama City’s bars really caught my imagination. Closer to the modern day, Panama was critical to the eradication of the screwworm in North America — an amazing feat that has been threatened by pandemic-era screwups.

Heck, even my favorite ants are from Panama. Azteca ants live in a close symbiotic relationship with cecropia trees, which have hollow stems. There, the ants build complex, multistory homes. In return, the ants defend the trees from caterpillars, birds, and other herbivores that like to snack on fruits, leaves, and flowers. They even go so far as to actively help repair damage to the trees.

All of which is to say that I keep coming across references to Panama, but honestly didn’t know much about it in a big-picture sense. Every time I tried to read the Wikipedia article, I got bogged down in minutiae.

My buddy RobRoy — one of the few friends I have who also read Banana by Dan Koeppel — put together a write-up on the Panama Canal crisis when he was trying to figure out what was going on, and was kind enough to share it with me. It’s not my habit to write about current events, but at this point most of the Panama Canal story is history, and he doesn’t have a blog. I find it all very interesting and wanted to share it with you. I’m grateful he’s letting me, and will share some of my thoughts at the end —

The Panama Canal has been suffering from a bit of a crisis. Many people aren’t familiar with what’s going on, and the problems are complex enough that I think it deserves a write-up. I’m going to break this up into how the canal fits into the modern world, talk a little bit about the history so we know how we got here, and then discuss the core problem we’re dealing with today and what the next steps look like.

First: Why we should care about the Panama Canal.

When a company has a container ship full of microchips in the Pacific that they want to bring to New York, or a shipment of Italian Maseratis they need to transport to Los Angeles they have two options to get them there… unless they would like to go around the world in the opposite direction. They can go around Cape Horn adding two and a half to three weeks to their trip, or they can go through the Panama Canal. Most people choose the canal.

Therefore, a significant chunk of world trade is reliant on this little shortcut. The Panama Canal is especially vital to US trade, with 40% of containers arriving into the US coming through that waterway. One example would be bringing goods from China, Japan, and Vietnam to ports on the east coast. But the Panama Canal isn’t exclusively of economic interest to the United States, it’s also a key strategic passage for our navy, and while a three-week delay might mean rotten bananas or more expensive Toyotas, for the navy, delays like that carry a cost in American lives.

While not every ship in the fleet can cross (as far as I can tell the Nimitz and Ford-class carriers are too big) most USN ships are built within the Panamax limit in mind, which is the maximum width a ship can be before it’s too big to pass through locks. Using the Panama Canal, the Navy can deploy its fleet faster, which causes far less wear and tear on ships, means shorter deployments for crews, and offers greater operational flexibility. In fact, the US signed a treaty with Panama guaranteeing the canal’s continued, permanent and neutral operation for all ships including military vessels to maintain our Navy’s strategic access to the canal and keep US trade lines open.

Second: How we got into this situation.

In 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa was the Spanish governor of Panama. He was based on the Atlantic coast, with no real understanding of what the Panamanian interior looked like. But from his native allies he began to hear rumors of the “Other Sea” and eventually undertook an expedition through the jungles and mountains to find it himself.

Upon his emergence onto the beach Balboa allegedly drew his sword and walked into the waters of the Pacific Ocean up to his knees. From there, he claimed possession of it and all its adjoining lands for Spain. Soon after dreams of building a canal to connect the two bodies of water began to take shape, although this was well before anyone had the technology or capacity to implement the plan. A few nations attempted it, including the French in 1880, but nobody was able to actually make it happen due to the inherent dangers of disease and challenges of geography.

In 1902, the US Congress voted to attempt to build the canal themselves, and while we originally tried to work with Colombia (who owned the region at the time) the Colombian congress wouldn’t agree to US financial terms. The US then assisted Panamanian rebels in revolting against Colombia. They formed a new nation, which immediately met US requests. In exchange for our help against Colombia, the US was given exclusive control of the Panama Canal Zone in perpetuity as part of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903. Construction of the Panama Canal was completed in 1914. Over the following decades political control of the now extremely lucrative canal became a major sore spot in US-Panama relations.

This culminated with riots in January of 1964. 4 US soldiers and 20-some Panamanian citizens died. This conflict eventually led to a new set of treaties 13 years later. The Torrijos–Carter Treaties set out a framework for the US to transfer control to the Panama Canal to Panama. The Torrijos–Carter Treaties were signed in 1977 and (among other things) planned to transfer full control of the Panama Canal to Panama in 1999. At that point Panama received the canal, and has been maintaining it for the past 20+ years without any major issues, and in fact even opened up the larger NeoPanamax canal lane in 2016.

So to summarize, the Panama Canal is an extremely important waterway built about 120 years ago, built and controlled by the US for about a hundred of those years and now controlled by Panama. On an average day, 36-38 ships will traverse the canal using the two Panamax and Neo-Panamax lanes.

Third: How the Panama Canal works (& fails).

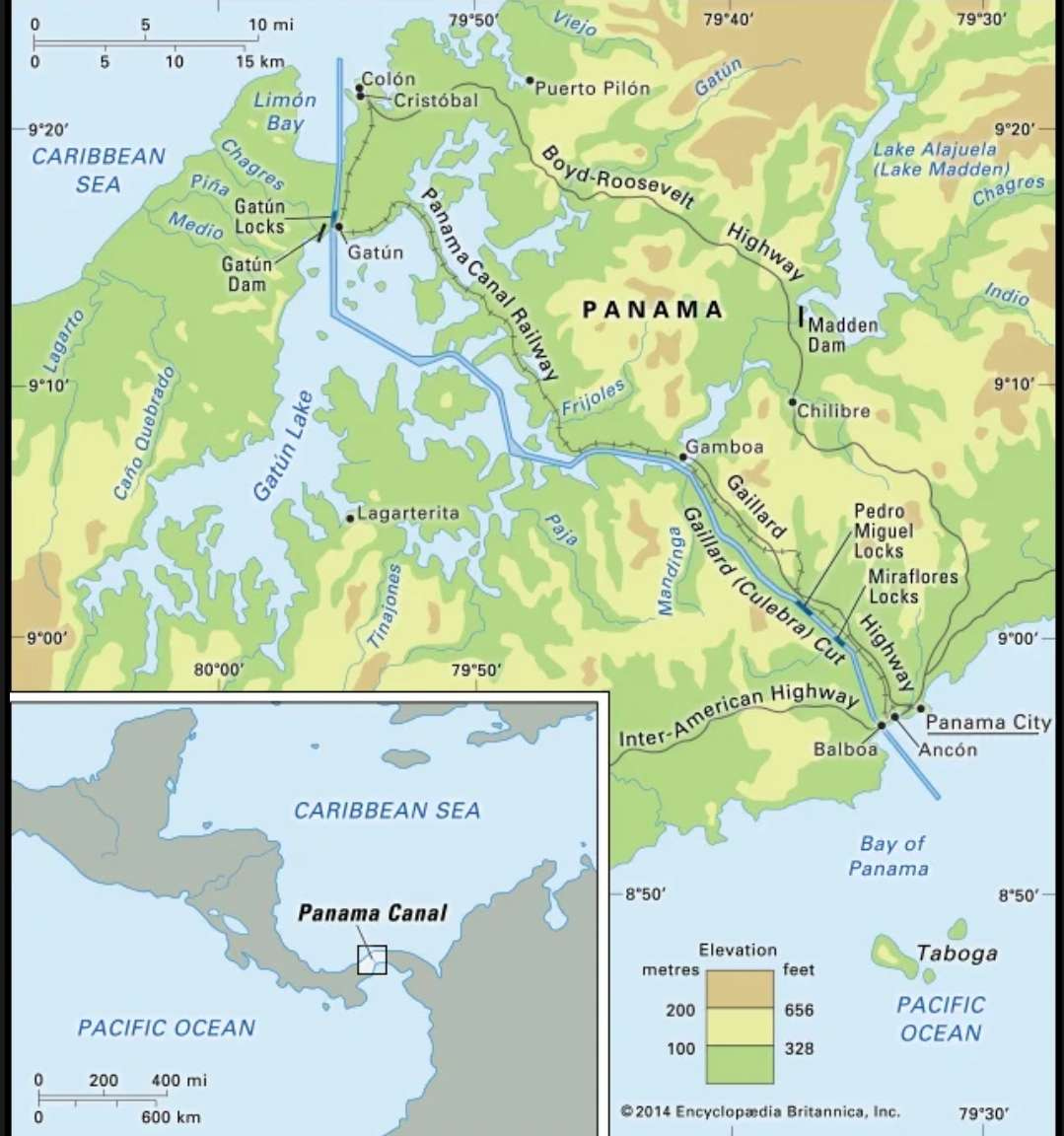

So Panama, despite being a thin isthmus, is actually a pretty mountainous country with a good deal of elevation change. When a ship wants to cross they’re initially lifted using a series of locks up to Lake Gatun, which is 85 feet above sea level. Then they spend most of the trip through Panama traveling across the lake and then coming back “down” the locks on the other side.

Now, two things are important to know about Lake Gatun. First, that it is the major source of fresh water for the people of Panama, especially people of Panama City. Second, that due to the way the locks work, it “costs” some of the lake’s water every time the water level in a lock gets changed.

According to the Panama Canal Authority it takes a total of around 51 million gallons of fresh water from Gatun to move a vessel through the canal. That brings us to the key problem: Lake Gatun is running out of water.

Typically, Panama has two seasons, a dry season (Dec-April) And a wet season (May-Nov) but in 2023 El Nino began and was unusually strong. El Niño is characterized by decreased rainfall which interrupted the 2023 rainy season and has caused a historic drought, resulting in Lake Gatun not getting sufficiently refilled, and over the dry season the water levels have continued to decrease due to transits. The Panama Canal drought crisis led to nearly half of vessel traffic being targeted for cuts. For example, the Panama Canal planned to limit transit to 32 total ships daily effective.

What makes this interesting is that this isn’t really a mismanagement issue, it isn’t really a maintenance issue, and it doesn’t really seem like there are many practical options to fix the situation.

The simple reality is that the canal was designed to use a certain amount of water to operate the locks and that requirement isn’t easily engineered away. To contextualize what this looks like from a trade perspective, during normal operation the Panama Canal will see 35-38 transits per day, but in July of 2023 year that number was limited to 32, and then in January 2024 that number was further limited to 24 transits a day. El Niño, despite being unusually strong, was expected to end within a few months. With a 79% chance to end sometime between April and June, the best-case scenario was El Niño ending early enough and a quick switch to La Niña such that the water level can be quickly restored. The worst-case scenario was El Niño didn’t end until July and a shortened or mild rainy season resulted in Lake Gatun not getting sufficiently refilled for the 2024‐2025 dry season. That would have led to Panama continuing to deal with transit restrictions until May 2025. All along the La Niña WATCH-tower is a nice historical source on how the uncertainty played out at the time.

Fourth: How can we mitigate the problem?

So the question is “What can be done?” and the answer is “Not much”. Yes, the Panama Canal got enmeshed in a crisis that’s disrupting global trade. But it will take years and billions of dollars to find a long-term fix.

From the perspective of the ships themselves, there are a few options. You can book a time slot in advance, you can wait in the queue of 100+ vessels sitting off the coast of Panama and wait a week for your turn, or you can pay to skip the line (up to $4 million in one case). Some ships are bypassing the canal entirely and are going around the Cape or even circumnavigating the world in the other direction through the Suez Canal — though that’s sometimes shut down for unrelated reasons, like that time the Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal for six days in March 2021. The cause then was a sandstorm — another natural disaster — and over 400 vessels were stranded.

On Panama’s end, due to some water recovery techniques used in the NeoPanamax locks, they’re able to recover 60% of the freshwater expenditure so there is a push to use that lane and larger, more efficient ships. But in the short- to medium-term, the Panama Canal doesn’t really have much ability to solve this issue.

In some senses, a “drought” is a temporary problem, but this crisis is couched in a larger conversation that climate change is going to lead to longer and stronger El Niño conditions. Longer and stronger droughts are probably coming.

If that does turn out to be the case, this situation will be the first of many. There is some thought being put into finding longer-term solutions to the issue. The most straightforward solution as far as I can tell is to dam the nearby Indio River and begin diverting its water to Lake Gatun. This should divert enough water to allow 11-15 additional transits per day, but that would take at least 6 years according to experts. This plan also faces opposition by people living where the reservoir would be built.

Another solution under discussion is building a third Panama Canal lane with the same efficiency improvements made in the NeoPanamax lane. Building another even wider canal using the same NeoPanamax technologies would improve the per-ship efficiency (by allowing larger ships through), while allowing the current less efficient Panama Canal to see decreased usage. There’s a conversation about doing this, but Panama just finished a major expansion and I don’t think it’s likely they will be starting another one anytime soon. As far as I can tell the conversations about it are aspirational.

Globally, a few other nations are hoping to take advantage of Panama’s issues by developing competing trade routes. The major proposals that I’m aware of are railways across Columbia, a highway across Paraguay and a competing canal in Nicaragua. It seems unlikely a railway or highway would help too much, but in general they are the kind of solutions that will help reduce congestion on the canal.

The Nicaraguan solution is the most interesting to me. Nicaragua would be a great location for a new canal from a geography perspective, and due to its flat topography it wouldn’t even need locks. In fact the US originally wanted to build the Panama Canal there in 1902. More recently the Chinese attempted to partner with Nicaragua to build it in 2015, but it seems to have gone nowhere due to corruption, mismanagement, and some financial setbacks faced by the chief financier. That said, the political situation in Nicaragua is the only real hurdle to making this a reality, and I wonder if the US will at some point make Nicaraguan stability a geopolitical priority.

Final Thoughts

Hearing about this situation made me even more concerned with the problems in the Red Sea because that means the two most heavily trafficked waterways in the world are at seriously reduced capacity. This has the capacity to really mess with the US economy, especially east coast prices. The supply chain ramifications are sort of obvious, but it isn’t actually clear to me what it means from a US consumer perspective. Due to contractual obligations, container ships get some sort of priority to move through the canal, so the impact might be primarily felt by manufacturers who require shipments of wet or dry bulk goods.

It’s difficult to really say how this impacted and will impact world trade or inflation, which are very complex systems. There are enough alternative solutions that trade won’t be cut off, it will just be slowed down or become more expensive. In any case this is an interesting crisis that isn’t getting the media attention it deserves due to the systemic nature of the issue and lack of a workable solution. Unfortunately the world is going to have to muddle through as best it can while we wait for nature to cooperate.

Right now, Iran is in the process of moving its capital due to a severe, multifaceted water crisis. Tehran’s dams are running dry. Rainfall has dropped far below the long-term average. Iran is experiencing its sixth consecutive year of drought and hottest summer in 60 years.

Pundits like to debate whether Iran’s problems are caused by climate change, government mismanagement, demographic change, or whatever. After looking into the history of famine for a previous article, my general opinion is that societies experience famine for a complex list of reasons. It’s rarely just one, there’s usually some combination of poor governance, war, and weather.

One reason I’ve been so interested in the Panama Canal, which I didn’t mention in the introduction, is that I live near the Key Bridge in Baltimore. It’s not nearly as vital a shipping lane as the Panama or Suez Canals3, but while I’ve been interested in trade infrastructure in the abstract for a long time, March 2022 and 2024 made it personal. If you don’t recognize the dates, that’s when a thousand-foot container ship Ever Forward ran aground in the Chesapeake Bay on its way to Norfolk. It was stuck for five weeks. Then, two years later, the container ship Dali rammed into the Francis Scott Key Bridge (of “Star Spangled Banner” fame) and took it down.

My local park shut down because search and rescue was based off the beach there. I took my kids to see the wreckage. The drive to my parents’ house now takes significantly longer, and my kids get sad because we have to go through the tunnel instead of over “best bridge.” My neighbors offices have relocated to make things easier on employees impacted by the commute changes.

According to the NTSB’s November 2025 final report, the root cause was a single loose wire in the ship’s electrical system that wasn’t fully inserted into its terminal block due to interference from wire-label banding. This caused unexpected breaker openings that triggered two blackouts, leaving the ship without propulsion and steering control.

But as a cursory perusal of the Hacker News discussion about the Key Bridge collision will show, the “root cause analysis” stops at the technical breaking point. But that’s not… really the “real” cause, in my opinion. The real cause was that the modern shipping system was designed for a very specific set of constraints and tradeoffs, and without “defense in depth” (and a certain amount of over-engineering), problems are going to happen.

Defense in depth is expensive, though… and as the Panama situation shows: sometimes there is no easy fix. For me, this is a bit scary, because as I watch the government dither and fight over rebuilding the Key Bridge, I have a visceral sense that if enough infrastructure problems crop up all at once, we’ll have a real issue maintaining the carrying capacity of our trade routes.

Frankly, given my understanding of the fall of Rome, that scares me a lot more than “mere” war.

Historian Bret Devereaux’s core argument is that the fall of the Western Roman Empire represented a massive reduction in the carrying capacity of the Mediterranean, especially western Europe, rather than a simple “barbarians killed everyone” story. In other words, the institutional and infrastructural collapse meant the land could no longer support anything like the late Roman population, so over the early Middle Ages the population shrank to match that lower ceiling.

When a population “shrinks,” it involves a lot of human suffering.

Under the Roman Empire, a dense network of cities, roads, ports, granaries, and administrative structures let grain, taxes, and goods move long distances efficiently, dramatically raising the effective carrying capacity of the Mediterranean world.

What we have now is much denser, much bigger, and involves much longer distances. The loss (or reduction in usefulness) of critical trade infrastructure like the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, and — closer to home — the Baltimore shipping lanes strikes me as much more worth paying attention to than most of the things people fight about on the internet.

I learned a lot from Banana… but as with many focused deep dive books, went of the rails at the end because it insisted on including alarmist environmental activist takes that… didn’t age well. The same thing happened with Coal: A Human History by Barbara Freese.

I ended up not finishing Lawrence because I find Lawrence himself so annoying. Part of the reason I wanted to share Rob’s notes is that all of my good opportunities to talk about Panama keep being stymied by the fact that my notes about it have been buried in notes on books I don’t plan to finish or review 😅

bean put together a really great write-up on the history of the Suez Canal. If you found this at all interesting, I highly recommend it.

That was so interesting, thank you! I knew some about the canal (since the infamous big container boat incident), but your write up filled all kinds of gaps i didn't know i had! I've never had to think about how just-enough types of manufacturing have effects on systems like this.!

I have told just about anyone who spends much time talking to me outside work or other official capacities about the ways I think that just-in-time manufacturing and other LEAN changes in our economies have left us open to far more risk than anyone realizes.

But I have never done anything in-depth to write it up or justify it, beyond stringing together a few anecdotes.

This post is a wonderful addition to my talking points and an example of the kind of work I could do myself to deepen my understanding.

Thank you for sharing it!