📗 Toy Problems Make Economics Easier To Grasp

I use fiction to understand the edges of real-world problems that confuse me -- like how libertarian free market theory accounts for the need for group defense, & the value of nerdy central planners.

I’ve always loved the art style of the “Little Golden Books” of my childhood, like this anti-safetyist message from the 70s (and yes, of course it’s an affiliate link). Anime and manga are fine, I guess, but graphic novels where I really like the art are pretty rare — offhand I can only think of Ursula Vernon’s Digger, which I am lucky enough to own a special edition of (because I bought it off Kickstarter for my husband on his birthday, good job past me).

I promised myself that I would write some fiction over Christmas break, and wanted to do something a little easier and looser than the graphic novel process I wrote about back in March.

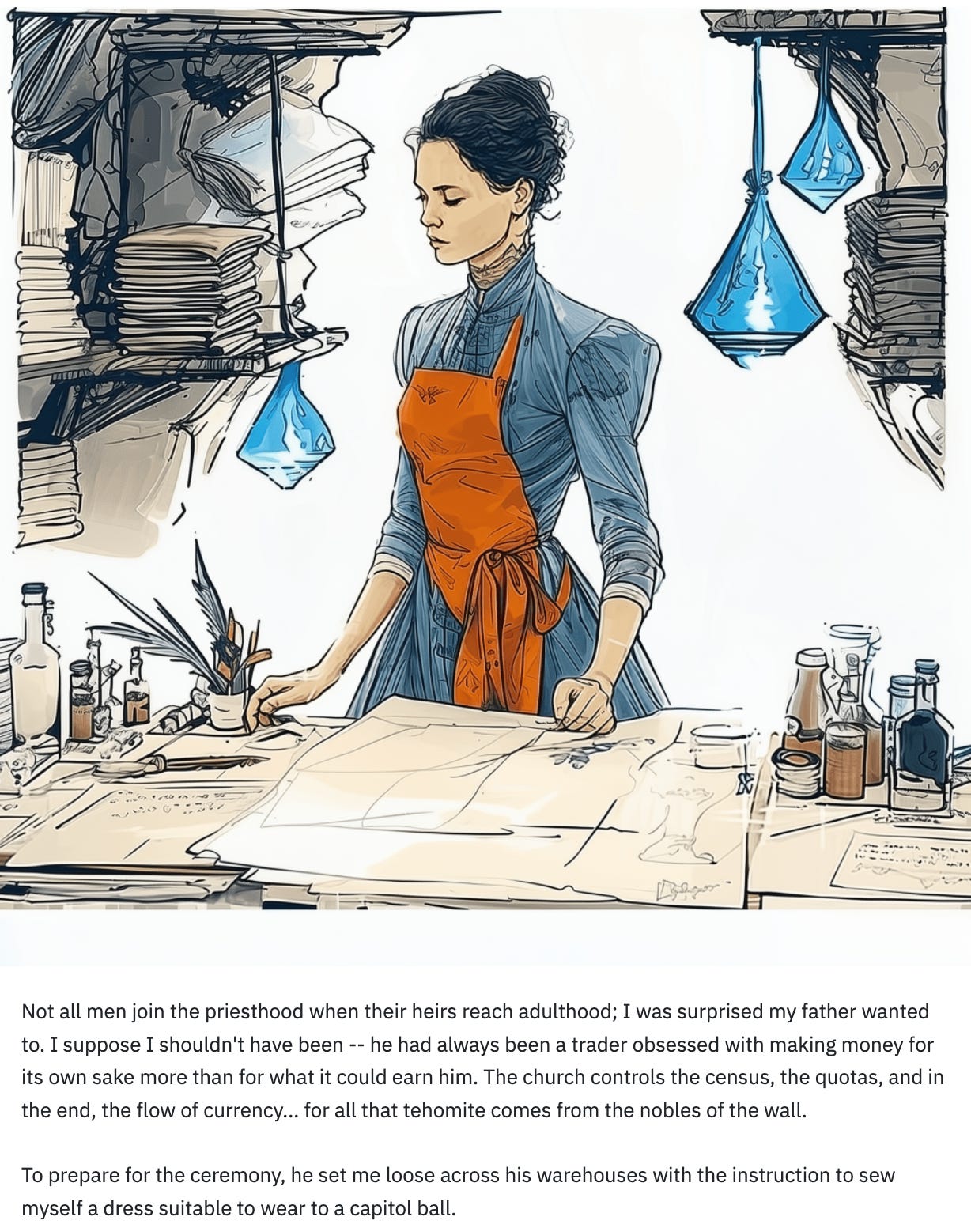

So I fired up Midjourney, dumped some of the outputs into my underused Pixelfed (decentralized instagram) account, and made decent progress on a story I like to think of as “Beauty and the Beast colonizing SPAAAAAAAAAAACE” but is actually called Maven and the Border Lord.

The framing story of the sketches I’ve been sharing is that they are taken from Maven’s notebook, which is horizontally oriented just like my favorite pocket notebooks. It would look something rather like this if embedding Pixelfed posts worked on Substack —

I am sharing this here not because I particularly expect most of you to follow along with what is essentially a serial microfiction story on a deeply niche platform (although there’s an RSS feed if you want to) but because the mere act of having a story I am working on vastly enriches my life, whether I am actively writing it or not… much less intending to publish it.

Last year, I resolved to build an exercise habit and enlisted my husband’s help to do it, because success in exercising works best for me if I don’t have to think about it. It worked great; I literally exercised as I wrote this article.

This year, I’m resolving to build out a “content calendar” (blech) for the whole year, stick to it, and actually find the time to write some (small) stories for the sadly derelict “fiction & addendums” section of my website.

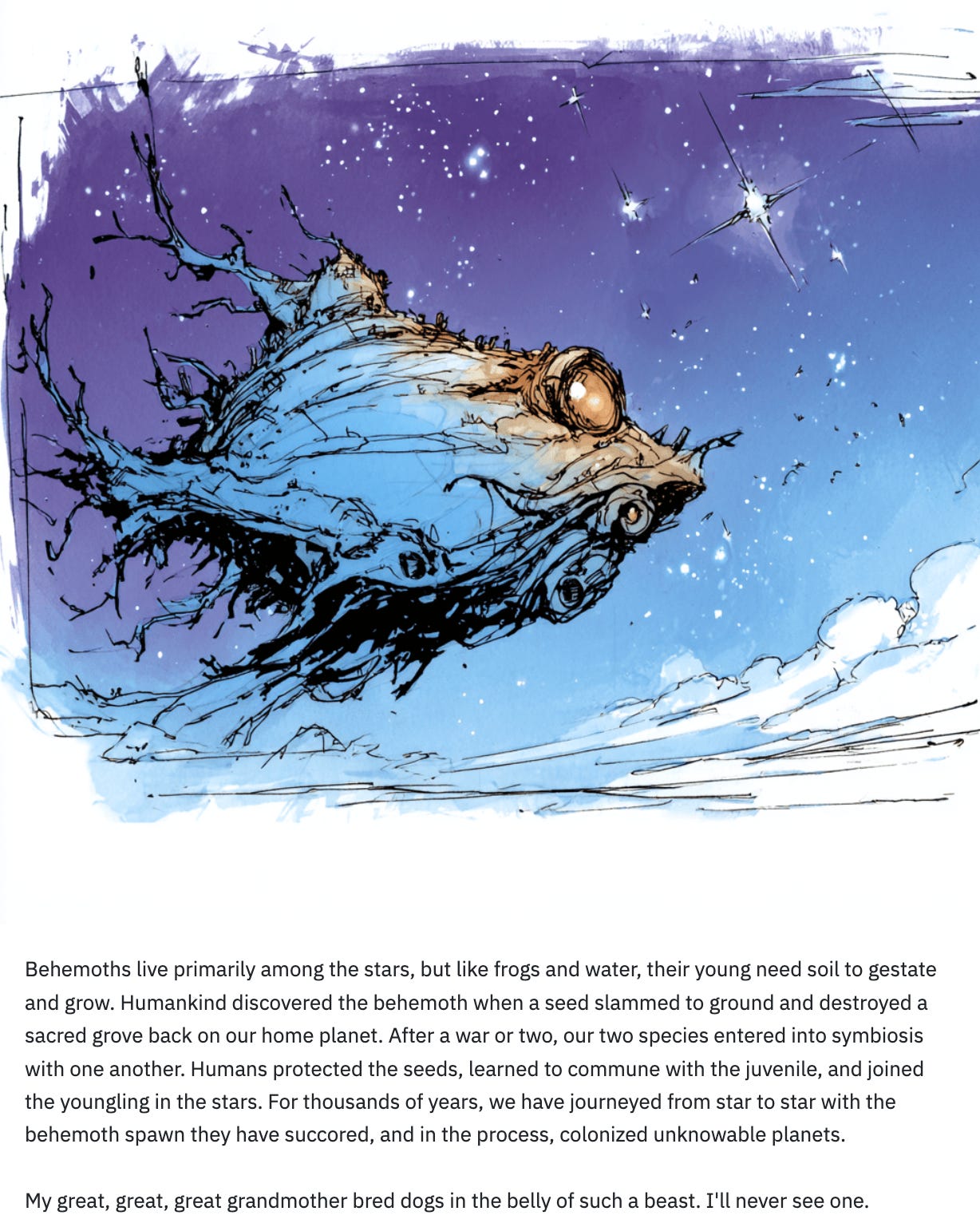

Chewing on worldbuilding questions is one of the primary ways I grapple with difficult questions; I believe very strongly in the value of sensemaking through fiction, although I am somewhat less enamored of New York Publishing and the Amazon distribution network than I used to be. The above segment about behemoths is inspired directly by the biblical behemoth, which I recently learned is sort of a mirror twin of the more famous leviathan from the Book of Job. But it also pulls in knowledge about amphibians I’ve been noodling on because my kids have a book with lots of frog pictures. It’s a reflection of my longstanding desire to write a colonization story, and the way my brain tries to reconcile science fiction and fantasy tropes while maintaining an internally consistent cosmos.

The biggest difficulty I’ve had so far with this story has been figuring out the economic system, which is to say the reason I’m so delighted by this story is that I’ve gotten to have so many interesting conversations about economic systems.

One of the core reasons I started taking notes and writing a weekly newsletter is that I wanted to have something to talk about with family and friends (and especially my husband) that wasn’t “all the frustrating things my kid did today.” My husband enjoys economics, and the day before a highly anticipated date night facilitated by his parents, I sent him the following question —

Imagine a world under constant threat from primordial chaos monsters — a specifically nonsentient, non-human force, like the Leviathans from A Tainted Cup1 or thread from the Pern books.

Now imagine that there is no central mint, and no military draft. There are hereditary nobles (with some relevant magic powers) guarding The Wall, which is a magical construct atop a mountain range that cradles a steppe plateau similar to the Eurasian plains. The people in this civilization set up an economy that rewards people for defense.

What does this look like?

In Pern, there were tithes that the large and crafters paid to the dragon riders to fight thread, but during the intervals (particularly the long one before the 9th pass), the civilians resisted paying and eventually the dragon riders had to use force in order to get their tithes.

The cowrie shells of East Africa are the only economic system that I really truly grok; they were explained to me as a fairly self regulating economic system; people would go harvest them when their value — mostly as status symbols like pearls or gemstone beads — was high, and do other work when their value is low.I’ve seen a system where the existential threat monsters have alchemical value, like the Tainted Cup where the leviathan body parts are how the society fuels its scientific advances and stuff, and the leviathans are so dangerous that absolutely no one could independently go beyond the walls and hunt one. They attack seasonally on a regular cadence so the value is pretty stable, and they get used up at a regular clip. But in that case, it takes the imperial army to fight one and the economy is controlled by the imperial bureaucracy.

One could imagine a situation more like beaver furs in the early colonial period, but with the caveat that they are overrunning the society like alpha beavers in RimWorld (a fantastic colony simulator if you’re not familiar with it) and need to be killed… but there’s a never ending supply that comes by randomly. But as I understand it, this would cause the opposite incentive I want: when there are lots and lots of alpha beavers, there would be less financial incentive to go hunt them even though there is more need to see them hunted… because there are so many that their value would go down.

You see a similar phenomenon with surge pricing for Uber and Lyft cars, when the prices go up the drivers don't drive more2... In many cases they stop right after they make “enough” money for the day and actually end up driving less than the otherwise might, which is a weird economic quirk of non-rational thinkers or something.

So if you’re trying to avoid a centralized imperial government with an imperial mint, but still incentivize through purely economic means dealing with a genuine existential threat...

...how do you go about it?

We spent a lovely three hours noodling over this problem (a much more fun topic than work problems or the chores we needed to get done). We discussed the ins and outs of communist central planning, the relevance of the Bureau of Labor Statistics for inflation, the gold standard, boom and bust cycles, vodka and cigarette economies, the importance of willingness to back taxation with military might in defense, how to determine what “enough” looks like in defense spending, Native American abundance ceremonies, and the degree to which “nerds with spreadsheets” are necessary for complex economies.

I had nearly given up on coming up with a self-regulating system — although my husband helpfully pointed out the obvious plot arc of a story set in the world I was describing, with a conclusion that I initially rejected but upon further reflection serves more of my goals than I realized — until on the walk home I had an epiphany and realized that I could swipe an idea from the incredibly excellent Cradle series by Will Wight (free on Kindle Unlimited, and the series is not only finished, the ending was great!) — specifically the way magical energy is condensed and used as currency — and put my own spin on it.

Yes, I know that’s a long sentence. It’s what happens when I am excited — you should hear me in person, I sound just like this!

Anyway, here’s the handful of words that three-hour discussion netted me:

Savvy readers will note that the detail about “their heirs reach adulthood” is a subtle nod to Suleiman and details about Ottoman rule I learned from Empress of the East, which I reviewed (favorably!) back in August. Giving up one’s worldly goods and joining the priesthood is also a real-world thing; Buddhist and Catholic traditions both emphasize renunciation of worldly goods through monastic vows or ordination, fostering detachment from material possessions to pursue spiritual goals. Mendicant orders like the Franciscans dispose of worldly items upon entry, prioritizing spiritual work over labor.

Maven’s father has made his fortune and secured bright futures for his children; now he wants to retire and help take care of a baby biological spaceship like all good nerds.

The neat thing about worldbuilding projects like this is that they allow you to create toy scenarios and discuss a wide variety of difficult problems without the baggage of trying to “actually” solve real-world problems. This is useful not so much because it lets you segue smoothly back into “well, for the sake of argument, let’s pretend there’s magic” and not have to worry about the logistical considerations of convincing 350 million Americans that your brilliant economic plan is a good one… but because it lets you break problems down into atomic components to understand them better.

When you learn about physics for the first time, teachers don’t couple air resistance and gravity and momentum and mass. They start with simple, pared-down problems, because they are easier to understand and hold in your mind.

Humans are not spherical cows, but I find that I have a lot more patience for sphere-shaped problems in economics, or pondering obscure religious details, or figuring out how to convey essential moral positions, when they are wrapped in obviously fake fantasy stories.

How about you?

I reviewed A Tainted Cup back in August as “On Corruption.” I had some quibbles about the epilogue, but finally got around to reading the sequel, A Drop of Corruption, and liked it more. It’s a fun little riff off of Sherlock Holmes, but with stellar worldbuilding in the “tower defense” genre. It won the World Fantasy Award and the Hugo, and honestly I think it’s deserved.

I learned this from The Cold Start Problem, which I read, and liked, and found useful for many applications beyond “building a startup” including corporate recruiting, social media platforms, and forming friend groups for kindergarteners. I have already recommended to several friends — but haven’t had a chance to review it.

This approach to grappling with economics through worldbuilding is clever. Stripping away real-world complexity to examine core incentive structures in isolation helps clarify whats actually driving the system. I've noticed the same thing happens when teaching concepts, building small toy models forces you tounderstand which variables actualy matter and which are just noise. The tehomite currency mechanic is a solid solution, tying defense directly to transactional value means the incentive structure aligns naturally.

This is off-topic, but I hope you will cross-post your book club here and not just on DSL.

I have resolved to not post on DSL, but would like to still engage with your projects.

I was going to make a similar request wrt your entertainment reaction log, but, honestly, I probably don't need the extra procrastination threads that would result (example: dissecting John Wick.)